The exhibition Oud Zeer highlights the often-hidden history of over two million Dutch people with roots in the Dutch East Indies/Indonesia. The portraits and stories show the family histories of people with roots in the Dutch East Indies/Indonesia – Indo-Dutch, Dutch (Totoks), Moluccans, Chinese from Indonesia (Peranakan), Indo-Africans and Papuans – from the first to the fourth generation.

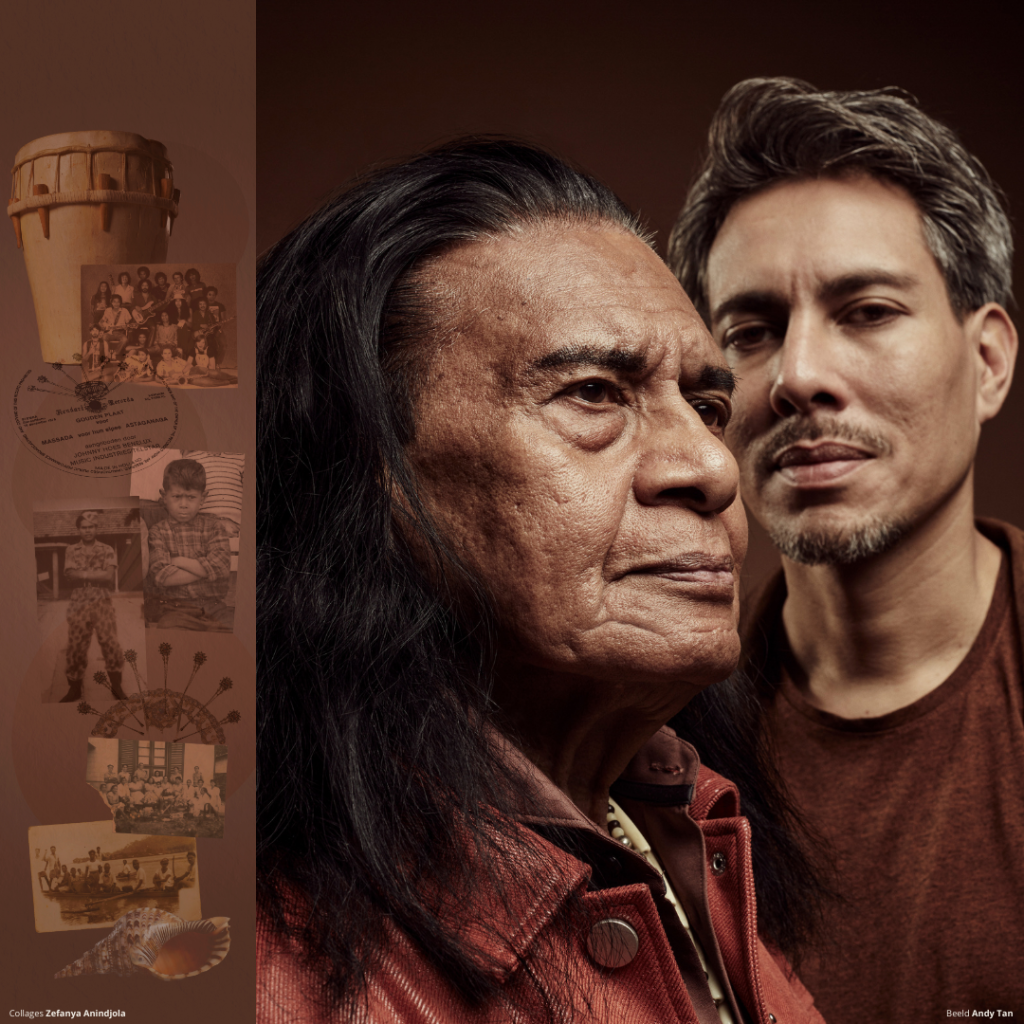

See and read the portraits and stories of Dido-Lisa, Elsbeth-Jorick, Wouter-Deja, Eefje-Milou, Ed-Jolanda, Corry-Raki, Vivian, Tony-David-Otis, Marius-Hedwig-Monique, Mary-Lisa, Meity-Jeremy, Hans-Rico-Rosa, Ruud-Sarah, Heiko, Malu-Arnold, Wendy-Chistien, Johnny-Diamo, Hans en Jan-Eva.

I DID IT DIFFERENTLY

LOST

JOHNNY: I belong to the second generation: the children who inherited the pain and frustration of the first. The soldiers of the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL) risked their lives for the Netherlands, but the government gave them no recognition. When they arrived here, there was no aftercare or support. As children, we had to absorb all of their frustration. Sometimes it came out as anger or aggression; sometimes as confusion, a sense of being lost. Some turned to drugs in search of a way to cope.

DIAMO: That was a generation that had fought for the Dutch flag. It was deeply frustrating for them to have fought so hard for a country, only to be met with such a cold reception when they arrived there. It’s no wonder that life was so hard for my father’s generation. They felt they had to make things right for their parents.

IMPACT

JOHNNY: My father rarely spoke about the Japanese occupation. When the family arrived in the Netherlands, they were placed in old military barracks, treated as if they were second-class citizens. They were unable to talk about it, let alone explain it. But what my father did bring home from his time as a prisoner of war was the way he disciplined us. These were no ordinary punishments: they mirrored the abuse he had endured during his captivity. Sometimes he would hang us from a beam half a meter off the ground and beat us. When he went out drinking to numb the pain of his memories, he would burn me with his cigars when he got home.

A FATHER WITH TWO FACES

JOHNNY: The book Astaganaga: 50 Years of Massada, which I wrote, is an ode to my father. He had two very different sides. One was kind, entrepreneurial and caring. But when frustration overwhelmed him and he turned to alcohol, he brought the war home with him. Whenever that happened, he would treat us like prisoners of war. For his grandchildren, he was the sweetest grandpa, but I never knew that version of him. My younger brother Eppie was unable to forgive him. It was only by learning more about my father’s past that I was finally able to forgive him on his deathbed.

DIAMO: Helping Dad with his book gave me a deeper understanding of his pain and of what his home life had been like.

SAVED BY MUSIC

JOHNNY: My main goal in life was to raise my children differently.

DIAMO: Music put my dad into contact with many Dutch organizations and people. It helped him open up, express himself more easily, and become more empathetic. That had a real impact on us, his three kids.

JOHNNY: My brother Eppie and I founded the band Massada. Without music, we might have ended up using drugs or engaging in crime. I’m incredibly proud of my children; they’re all very creative and musical. Without being pushed, they embraced that same pride. They knew: if Dad could do it, so could they.

DIAMO: Dad is a powerful example of how you can turn pain and frustration into something creative. That’s something I try to carry into my own work and pass on to my children. Being able to turn struggle into positive action is a gift we can hand down to future generations. I hope it helps them heal and saves them from having to deal with the pain and frustration our parents had to face.

KNOWING WHERE YOU COME FROM

I HAD NO YOUTH

ED: My youth ended abruptly at the age of seventeen. In early 1942, I was cruelly separated from my family: my Dutch father, Chinese mother, older brother, and three sisters. After Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, I was drafted into military service and soon after, I was taken prisoner of war. I was sent to Burma, now Myanmar, via Singapore on a Japanese “hell ship” (transport ship). In the overcrowded hold, there was only room to sit or lie down. During my three-and-a-half years of forced labour on the Burma-Siam Railway, I was constantly hungry. It was more than four years before I was briefly able to visit my mother and sisters in Batavia after being stationed in Surabaya.

DISCRIMINATION

JOLANDA: My father never spoke about the past. As a little girl, I used to wonder whether my family came from India or the Dutch East Indies: I didn’t even know. If my dad said anything at all about the past, all his stories started after the liberation. He would talk about the Netherlands, where he continued his studies in 1948.

ED: It took me just three-and-a-half years to complete technical college (HTS). I had hoped to continue my studies at Delft University of Technology, but I wasn’t admitted. I felt discriminated against by the admissions committee. Later, at Philips, where I spent my entire career, I earned less than my Dutch colleagues doing the same work, and I had fewer opportunities for promotion.

JOLANDA: In 2013, my father and I travelled to Thailand with other Dutch East Indies veterans on a trip organized by the Foundation for the Commemoration of the Burma-Siam and Pakan-Baroe Railways. During this trip, he talked about his imprisonment for the first time in his life.

ED: The camaraderie on that trip meant so much to me; it was something I missed in the Netherlands.

A HUGE BLANK

JOLANDA: Although my father was always incredibly caring, he never showed his emotions. At home, I was never taught to stand up for myself. Some things he let slip later helped me to understand why. During his imprisonment, for example, he had learned to keep his head down to avoid being noticed. After finishing my studies, I began looking for answers. For a long time, our family history felt like a huge blank. I used to think, “My family wasn’t there that long, as Grandpa only arrived in the Indies in 1918.” Only recently did I realize that my Chinese grandmother had a long family history in the Dutch East Indies, now Indonesia. I had effectively erased her; she didn’t count in my view of our family history. I’m now trying to learn more about her life and family.

A LESS HARSH LIFE

ED: Looking back on my life, there were so many obstacles to my development. I hope this generation can lead a less harsh life, free from such barriers.

JOLANDA: Now that I’ve written a book about my family, I have a clearer picture of my father, and a greater understanding of what he went through and why he was so silent. When my niece and nephew are older, they’ll be able to discover their roots and what life was like in the past, so they’ll have fewer gaps in their family story. Ultimately, this shapes your character and identity. We, the postwar generation, share a common history. It’s comforting to know I’m not the only one with this ‘struggle’, growing up with a father who was unable to talk about his experiences.

NOT BEING SEEN

A GREAT BLACK HOLE

JORICK: Grandpa and I shared a love of gardening, something he’d enjoyed as a child before the war. But he never told me anything about his childhood. I regret that he never shared his experiences with me.

ELSBETH: My father simply couldn’t talk about it. About four years before he died, he said: “There are so many children’s books about the Second World War, but they’re all set in Europe. You are a children’s author: would you tell my story?” I was deeply moved that he was willing to entrust this to me, but it also came as a shock to realize how little I knew about his early life. It had always been a great black hole, overshadowing my childhood and adult life. But writing about it made that emptiness disappear. The sense of relief was immense.

UTTERLY ALONE

ELSBETH: During the Japanese occupation, my grandmother was held in two different women’s camps with her two children. When my father turned thirteen, he was forcibly separated from his mother and younger sister by the Japanese and sent to survive in a men’s camp. After the liberation, he visited his father in the hospital every day even though the city was being shelled and bombed from all sides. Despite these desperate conditions, the family managed to flee to the Netherlands in late 1945 aboard the hospital ship Oranje.

BREAKING AWAY

ELSBETH: I was a real daddy’s girl. My father always gave me a lot of attention and affection. But all that changed when I was around thirteen and he went to Indonesia. He came back a changed man. I just couldn’t understand it. I was just hitting puberty and wanted to enjoy life. I wanted my old dad back, but it felt like Indonesia had stolen him from me. He became withdrawn and often lost his temper. Because of his camp trauma, I felt unseen. With all the tension at home, I pushed myself to get perfect grades and avoided the usual teenage rebellion.

JORICK: I actually rebelled more as a teenager and pushed back against my mother.

ELSBETH: When my own kids hit puberty, I told myself: it’s actually good that they are doing this now, otherwise they’d have to break away from you later. But I found it incredibly hard. I’d never had any experience with that.

JORICK: My mom’s book about Grandpa’s traumatic wartime childhood shed light on a lot of things. It gave me a better understanding of both of them.

MORE UNDERSTANDING

ELSBETH: I hope that one day there will be as much understanding for the war in Asia as there is for the war in Europe. I also want recognition for the families from Asia, who tried to rebuild their lives when they arrived here, even if they did not always manage to do so, or were not successful in the long term. I also want recognition for us, the postwar generation. Growing up with the weight of the past was very hard, no matter how much I loved my father.

JORICK: Sharing these experiences gives me strength. The worst things I go through seem so trivial compared to what Grandpa survived. If he could survive, then so can I. He stayed in survival mode for so long, but he persevered, and that inspires me.

ELSBETH: I wish I could have said to my father: “I didn’t give you enough credit back then. It’s only now that I can understand how terrifying and traumatic it was, and why you couldn’t always be there for me.”

NO STABLE FOUNDATION

DISRUPTED

HANS: My childhood ended when the war in the Dutch East Indies − now Indonesia − began. My father was imprisoned in an internment camp. My mother and we children stayed outside the camp, taking shelter in a small hut raised on stilts that was otherwise completely empty. We were constantly hungry, suffered severe bouts of malaria, and lived in fear of both the Japanese and the Indonesians. My mother was in poor health and often ill; she rarely left the hut. My three older brothers were forced to work for the Japanese, so I barely saw them. Our family felt like loose sand that couldn’t hold together. I spent most of my days sitting on the steps outside. When I was indoors, I could only see the world through the gaps in the walls. That’s how I lived from the age of two-and-a-half to six.

NO ROOM FOR FEELINGS

HANS: During the war years, there was no stable foundation on which I could build my life, and that was never remedied. After the war ended, the so-called Bersiap period began, and we were threatened by Indonesian freedom fighters. The continued violence eventually forced us to flee to the Netherlands in 1947. But when our family was finally reunited there, a different kind of war began for me. We were placed in a rough neighbourhood, and my parents could no longer live peacefully together. Our family was broken, and there was no room for my emotions. It was not until 2007 that the Dutch government finally gave some acknowledgement of the wartime experiences of buitenkampers. **.

ROSA: My father and his brother both wrote books about their memories. That’s how I found out what had happened. When I travelled to Indonesia, I asked my dad some questions, but I was afraid to push too hard. His emotions would become so intense that he shut down completely.

A SENSE OF JUSTICE

ROSA: Dad has always carried a kind of anger toward authority, capitalism, and general inequality. That feeling really comes from deep inside him.

RICO: Dad looks out for the underdog. I think that’s played a huge role in shaping his path in life: first through student activism, now through climate action. It’s rooted in the idea that the injustice you suffered shouldn’t be inflicted on others. That sense of justice is something we inherited from him. We learned that it’s important to stay aware of your responsibility to respond to what’s happening in the world.

THE SWEETEST DAD

RICO: I’m really glad our family history has been written down and shared with us so we can keep exploring it for the rest of our lives. It also makes it easier to be there for Dad and to talk to our parents about it.

ROSA: I’m grateful to be an adult in a time when there’s space in society for these conversations. That means so much to me. And I can tell that it does Dad good. Even though it’s much too late, there is finally more room for these conversations.

RICO: It’s an incredible story; how someone who lived alone for years in a tiny hut went on to function so well in society.

ROSA: It’s an absolute miracle that he managed to be such a loving parent, despite everything he went through. I always felt 100% seen and cared for.

RICO: Dad is truly the sweetest father you could imagine. He’s always there for us.

HANS: I’m happy as long as my children and grandchildren are happy, and that they don’t have to go through a war themselves.

*Bersiap: The extremely violent months at the start of the Indonesian Revolution. “Bersiap” (“Be ready”) was the rallying cry of Indonesian freedom fighters.· Buitenkampers were Indo-Europeans who weren’t interned in Japanese camps. People often wrongly assumed they had an easy time during the war, but they also faced extreme hardship, exclusion, scarcity, and repression. After 15 August 1945 they were left unprotected, at the mercy of hostile nationalists fighting for independence.

BUILDING BRIDGES BETWEEN GENERATIONS

SURVIVAL

My grandmother always used to say, “My biggest trauma is that I don’t have a trauma.” She was an incredibly strong woman, the kind who believed you just had to keep going. Of course, that was also a survival mechanism, because so much had happened in her life. Sometimes, when she spoke about the Japanese occupation and the struggle for independence that followed, I could hear the sadness and fear in her voice. My Indo grandparents were both writers and journalists, so they told me a lot about their former lives and their experiences during the war. My grandfather was a prisoner of war in three camps, where he endured extreme hunger, and my grandmother had to endure great hardship as a non-internee* during the Japanese occupation.

DISPLACEMENT

In the Netherlands, my grandparents ended up in two contract boarding houses, where it was cold and miserable. My grandmother described how she felt standing on Dam Square in Amsterdam with her children: “Not so long ago, we were running around barefoot on the farm. Now we’re here in the cold, wrapped up in stiff, heavy coats and hats.” The contrast couldn’t have been greater. There was a deep sense of displacement. First you leave a home where you’re no longer welcome. Then you arrive in a country where you’re officially a citizen, but it doesn’t feel like home. Wanting to give a voice to all the Indo-Dutch people who felt the same way, my grandfather started his own magazine. It was a way to speak out, to share that sense of dislocation, and to build a sense of connection.

BEING INDO

My cradle quite literally stood in the editorial office of the magazine Tong Tong (now Moesson). My grandparents lived in the same building in The Hague. The editorial team, the volunteers, and all the ‘uncles’ and ‘aunts’ who spoiled me felt like one big family. From a young age, being Indo was simply part of who I was. After my grandfather passed away, my grandmother continued the work with help from my father. It wasn’t until she died as well that I truly understood what a remarkable legacy they had created with the magazine, and how unique that history is. In time, I took up the baton, and I will do everything I can to honour and protect their legacy.

MORE AWARENESS

When people first arrived in the Netherlands, they were often met with comments like, “At least you lived in a warm country during the war, with bananas growing on the trees.” It showed just how little people understood about what that generation had actually been through. There was no awareness of the horrors they had faced, or what it meant to have to start over completely in a new country. That lack of recognition is part of the pain the community still carries today. With Moesson, I try to connect the generations and help them understand one another. I want to show what it was like for the first generation and how young people experience their identity now. Not everyone grew up, like I did, in a family where the past was openly discussed. It would be nice if people knew more about the hardships, perseverance, courage, and above all, resilience of this community.

*Non-internees were Indo-Europeans who were not interned; it was often wrongly assumed that they had suffered little during the war. In fact, they faced severe hardship, exclusion, scarcity, and repression. After 15 August 1945, with no camps or guards to protect them, they were defenceless against hostile nationalists fighting for independence.

BREAKING PATTERNS

FLASHBACKS

CHRISTIEN: I was born in Jakarta. In 1954, when I was four, my parents decided to move to the Netherlands for a better future. My mother had to leave her mother and brother behind. Sometimes my parents would share happy memories, but they never spoke about the war in the former Dutch East Indies/Indonesia. All that changed when my mother, late on in her life, said she wanted to return one last time. During the trip she experienced flashbacks, and became very emotional: she remembered everything. I shed many a tear myself.

WENDY: When I first visited Indonesia at the age of 22, I felt that my roots were there. It’s a feeling you can’t really explain.

OLD WOUNDS

WENDY: Being at Grandpa and Grandma’s was always lovely: there was food, dancing, and guitar and ukulele playing. But old pain was never discussed, especially anything related to the Japanese period. I still remember the spooky ghost stories and the sense that there’s more between heaven and earth.

CHRISTIEN: My mother wanted to have fun. She loved cooking, dancing, eating: all the things that she had missed out on earlier.

WENDY: As a young woman in war time, Grandma was forced to live in a world that stole her innocence. She had no choice but to survive.

CHRISTIEN: She never revealed exactly what had happened to her. Maybe it was to protect us, or maybe because some wounds are too deep to express in words. Looking back, I realize that all that laughing, dancing, and cooking were her ways of suppressing her pain. She couldn’t show her love with hugs or caresses, because she had never known that herself. She showed her love for us through her cooking.

WENDY: Your love for us is something that we’ve always felt.

CHRISTIEN: I did my best because I wanted to give my three children what I had missed out on myself.

IMPACT

CHRISTIEN: Around the age of sixteen, my father’s health began to deteriorate. Whenever he saw a war film on TV, he became so upset we had to turn it off. My brothers and sisters still remember how emaciated our father was when he returned after the war after serving in the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL).

WENDY: Both of my grandfathers served in the KNIL. I can’t imagine what it must do to you as a child to see your father come home so broken by war. Later on, I was sorry that I had not asked them more about what the Japanese occupation had been like for them.

HEALING

WENDY: Our whole family makes music: it brings us joy and healing. As a DJ/producer, I love playing music and sharing beautiful sounds and melodies. Music is magical, it connects people. Words are not even necessary.

CHRISTIEN: Back then, we didn’t talk about our feelings, so I kept everything to myself. But we have learnt from this. We now know that it’s important to talk about what’s on your mind, because silence can cause so many problems. Above all, remember that you can always ask for help.

WENDY: Talking and asking questions helps us to understand more about that old pain, so that the pieces of the puzzle start to fall into place. One thing is certain: our grandparents bore their pain with dignity.

KEEPING YOUR DISTANCE

NEVER OVER

It’s easy to become trapped in a painful past: once it takes hold, it never really lets go of you. Letting go of the war has always been difficult for me. I’ve never felt guilt, since it was my grandfather’s war, not mine. Still, over the years, I have felt a growing pressure. There is a constant expectation to acknowledge the brutality of the independence struggle, and to recognize the blood my grandfather, as a KNIL officer, had on his hands. At the end of the day, I’m left grappling with the fact that my grandfather was ultimately responsible for many thousands of deaths.

AMUSING STORIES

My grandfather on my mother’s side was a general. I thought that was super cool and I would brag about it at school. My grandparents hardly told me anything else. I knew my grandfather had been an excellent marksman. When we were out walking the dog in the woods, he’d suddenly say, “What do you hear?” Then he’d tell me what you would hear on patrol in the jungle in Sumatra and what animals lived there. They were kind of campfire stories that amused me at the time. But now I think, they were all about violence.

ESCAPING THE WAR

Because my grandparents and their children took extended leave to the Netherlands in 1938, they narrowly escaped being interned by the Japanese during World War II. My grandfather, an officer, worked at the ministry in The Hague. When the Germans occupied the Netherlands, he refused to sign the parole declaration required by the Nazis and spent five years as a prisoner of war. After the war ended, he had just one goal: to “punch the Jap in the face.” But when he finally returned to Indonesia, the Japanese were no longer in power. Instead, he found himself fighting against Indonesians who were struggling for their country’s independence.

SHAME

As a historian, I spent twenty years presenting a TV programme called Andere Tijden (Other Times). It is based on two pillars: eyewitness accounts and archival footage. I’d been working on it for about five years when a director handed me a videotape and said, “Take a look at this. Is that your grandfather?” I still remember the shock that went through me. Only then, when I was already forty, did I begin to explore my own Indo-European family history. As a historian, I find it quite embarrassing that I waited so long.

ONE MORE CONVERSATION

It was then that I realized that Grandpa’s story wasn’t as harmless as it seemed. I didn’t want to get too close. We weren’t close anyway, because my brothers and I always thought he was very right-wing and reactionary. I was left-wing and had long hair. I looked down on Grandpa because I thought he didn’t understand the world. But when I saw that archival footage, I was struck by the realization that he had really been through something significant. And I had picked fights with him, even though I had never experienced anything myself. It’s embarrassing to think about. Now I would really like to talk to him about it. His perspective isn’t mine, but I want to try to understand it. What was it like for him? And how do you live the rest of your life after being responsible for all those thousands of deaths?

FILLING IN THE MISSING CHAPTER

NO FUTURE

RUUD: My father fled to the Netherlands in 1958 at the age of 24, hidden aboard the ship Johan van Oldenbarnevelt with other stowaways. As a young Moluccan, he saw no future for himself in Indonesia. On arrival, he was detained at a centre for Indonesian stowaways in Doetinchem. The government intended to send them back to Indonesia, but Mrs Ten Broecke Hoekstra of the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) strongly opposed this in parliament, warning: “If you send these boys back, you’ll have blood on your hands.” In the end, 37 stowaways, including 30 Moluccans, were sent to New Guinea, which was still Dutch territory at that time. My father returned to the Netherlands in 1962, carrying his belongings in a single suitcase, determined to build a new life.

SARAH: In recent years, I’ve really immersed myself in that history. I keep asking myself: what kind of blood flows through my veins, and what happened to my family?

THIS IS MY FAMILY

RUUD: The stowaways formed a close-knit group. They were like family to me throughout my childhood. Two of my father’s uncles, who had also ended up in the Netherlands, became my grandfathers. My father used to say, “I came here to build a new life.” We were never really told much about the past, but I did learn how important family is. That connection with one another is what matters most to me.

SARAH: For me too, family always comes first. I know they’ll always be there for me and have my back.

QUESTIONS

SARAH: It wasn’t until I went to drama school that I started noticing I looked different. No one could pronounce my “difficult” last name properly either. I began to wonder what Moluccan history was all about. I hadn’t learned anything about it at school, and it wasn’t really discussed at home. I find it difficult that so much has been left unsaid. Because of that, my generation is left with questions. When I say, “I’m Moluccan,” people ask, “From that train hijacking?” Why is it that when people talk about Moluccans, it’s nearly always something negative? The real history isn’t in the textbooks. It’s a missing chapter, and we need to fill it with our stories by creating spaces where we can speak up and show what really happened. Our generation feels a fire inside. We know we have to do this now, before the opportunity is lost. That’s why I chose to go into theatre: to create a space for myself and others to be heard, so that everyone can feel free to be themselves.

RUUD: I’m very proud of that. This generation is going to make sure that this missing chapter gets filled in, to show what Moluccans have achieved; they have fought for this.

MAKING SPACE FOR UNHEARD STORIES

SARAH: Theatre gives me a way to tell those stories. It helps you explore who you are and how you feel. Talking about things helps you to become more comfortable in your own skin, and that makes it easier to connect with others.

RUUD: And show that we are proud of what the Moluccan community has achieved. Despite all the pain of both the past and the present.

SARAH: Indeed, we should all be able to say: “Look at how well we’re doing together and how hard we’re working to tell all these stories that have never been heard.”

KEEP TELLING THE STORY

THE PROMISED LAND

EVA: I grew up with the Moluccan culture, and I was curious about our family history from an early age. My mother told me a lot about it, and this prompted me to start asking Grandpa questions. He would tell me about the war, how every morning at school they had to raise the Japanese flag. He could still sing Japanese songs and taught me to count to ten in Japanese.

JAN: I was five years old when the Japanese invaded the Dutch East Indies/Indonesia. We always had to be careful to bow to the Japanese soldiers in time. My father was a sergeant in the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL), and we didn’t know where he was. In 1951, when I was fourteen, we went to the Netherlands “temporarily” because of the political tensions between the Netherlands and Indonesia. During the sea voyage through the Suez Canal, the elders would pray facing Mount Sinai. Moses led the Jewish people to the promised land. The elders thought that one day they would return to a free Republic of the South Moluccas.

STRICT

EVA: It’s painful for me to imagine what that “temporary” departure must have been like for my grandparents and great-grandparents. We still have my great-grandfather’s army trunk; that’s all they brought with them. My mother and I lived with Grandpa until I was seven. My upbringing was strict, even militaristic at times, especially compared to Dutch kids. If I couldn’t sleep, I had to do squats in the hallway until I was tired.

JAN: Eva was very upset when my daughter Amda got her own house. I still used to pick her up three times a week for lunch.

EVA: My grandpa worked hard for our family and our future. We spent a lot of time together and often went on trips. I feel less connected to people who don’t know our culture and history as they often have a very different outlook on life. When I’m with my cousins, I don’t have to explain anything, and that’s nice.

PERSEVERANCE

EVA: It’s important for schools to teach young people why Moluccans came to the Netherlands and what happened in the past. That part of history is still largely missing from the curriculum. My family came from far away. They’re all strong, resiliant people, and I try to be one too. But I often feel a sense of restlessness. Where do I truly belong? Here in the Netherlands, I’m often misunderstood because people don’t know much about my background or how I was raised. Still, I’ve learned to adapt wherever I go.

JAN: My father didn’t want to stay in the Netherlands; he wanted to return to the family he’d left behind. He stayed here to give his children a better future. My roots are in the Moluccas, but I also wanted to build a future for our family here.

EVA: Studying at Utrecht University is a true privilege. I don’t think my great-grandfather or grandpa ever imagined anything like that. It’s only possible because they built a life here through their hard work and perseverance. I’m very grateful for that, and above all, I’m proud of my close bond with Grandpa.

JAN: I’m grateful I was able to give Eva positive encouragement to build her future.

POSTSCRIPT

EVA: After my grandpa passed away on January 19, one-and-a-half months after this interview, I found his application for WUBO compensation. It described his traumatic experiences during World War II and the Indonesian War of Independence. Grandpa mostly talked about the “great” time he had had in Barracks 2B in Vught, and rarely mentioned the hardships he had endured during the wars. Only now am I discovering his old pain.

PROUD OF MY HERITAGE

CURIOUS

WOUTER: I’m Dutch, with Indo-African roots. As a child, I often felt different because of the way I looked, and I felt a deep connection to my Indo-African grandparents. My great-grandfather, who was born in West Africa, was recruited by the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL) to serve as a soldier in the Dutch East Indies, now Indonesia. I was always curious about my grandfather’s life. I wanted to know everything about his childhood and his parents, and I often wondered what life was like for the other African families living on Java. My own family lived in Kampong Afrika, a village in Poerworedjo.

A NEW LIFE

WOUTER: After arriving in the Netherlands, my grandparents had to start all over again. It must have been an enormous challenge. My grandfather was intelligent and ambitious, but he was held back because the Dutch diplomas he had earned in the colony were not recognized, which meant he was unable to access certain jobs. In the end, he continued to study for the rest of his life. My brothers and I could feel the impact of that past. Our mother was firm about the importance of doing well at school. High grades were important.

SURVIVAL

WOUTER: For my mother’s generation, there was little space to talk about the colonial past or reflect on identity. She had to assimilate and focus on survival. As part of the third generation, I see that there is now more freedom to explore who we are. We are free. We are no longer trapped, and we don’t live in a colony. But the legacy of the colonial past is still with us. I feel it in my own search for identity, and in the way society continues to define me and others.

A SPECIAL MISSION

WOUTER: Grandpa was taken prisoner by the Japanese as a nineteen-year-old and was forced to work on the notorious Burma-Siam railway.

DEJA: I’m glad that Grandpa was freed and could live in the Netherlands.

WOUTER: In 2013, we went together to Thailand and Burma (now Myanmar) to fulfil my grandfather’s long-held wish to visit his brother’s grave at the Thanbyuzayat War Cemetery. There, my grandfather asked me if I would pass on the stories of our family history. This now feels like my life’s mission. This is how I process the pain and sorrow of my family’s past.

DEJA: That’s why I made a beautiful Melati (Indonesian jasmine) wreath for the commemoration.

BE YOURSELF

DEJA: Mom is from Suriname, grandma Hilda and dad’s father are from Indonesia. But we’re also African. That’s a lot of different countries! I’m proud of my hair and eyes.

WOUTER: I’ve spent a long time searching for my identity and a place where I truly feel at home. The older I get, the more important it becomes to me to be proud of who you are. That’s what I want to pass on to my daughter, Deja: know where you come from and always stay true to yourself. It’s why I believe our family history must never be forgotten and should be passed down through the generations. As part of the third generation, we carry the pain that has been handed down to us. I want to heal that pain so my daughter doesn’t have to face the same struggles.

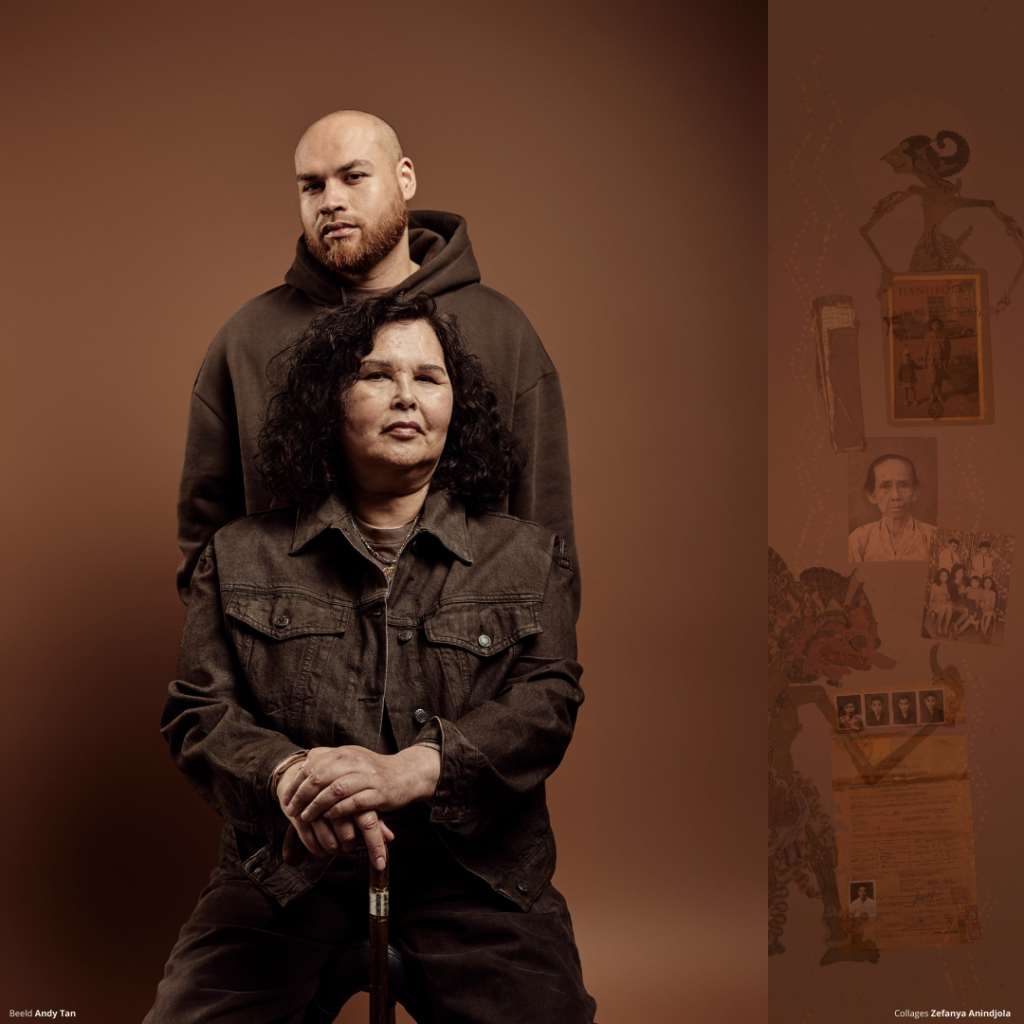

DEFIANT AND HOPEFUL

FLED

RAKI: I was afraid to admit that I was from West Papua until I was 21 as people would crack stupid jokes whenever Papua was mentioned. The situation that had forced my mother to flee to the Netherlands with us was a defining aspect of our upbringing and my life. We talked about it almost every day. But here in the Netherlands, no one knew anything about West Papua; the story of our identity had been erased. Things began to change when I started asking questions about who I really am. I talked to people of Indo and Moluccan heritage, and interviewed my mother, aunts and uncles. I had to because this topic was never taught at school. Learning about my heritage was a huge turning point and became a source of strength for me. I learnt that we are the people of the world’s largest tropical island, with a rich culture we should be proud of. That’s how to create a different story.

WHERE’S MY FATHER?

RAKI: My mother fled West Papua* in a prauw (boat) with three young children. I was born in a refugee camp on the eastern side of the island. After the Indonesian takeover in 1962, we lived in constant uncertainty, partly because our father was in prison and we were receiving threats. In 1985, we arrived in the Netherlands, which, as the former colonizer, granted us asylum. We were embraced and supported by the Papuan community, which eagerly followed and engaged with the events unfolding in West Papua. Right from day one, after my mother appeared in a newspaper article, we talked openly about the situation at home and discussed what we could do to try to improve it.

CORRY: The only thing we did not talk about was the death of Arnold, their father; that was too much for the children. This went on until Raki was five, and asked me: “Mama, where is Papa? When is he coming home?” It was time to tell them. I took his hand and said: “Papa isn’t coming home. Papa was murdered.”

RAKI: It wasn’t until many years later that she showed me and my three brothers the photos of how he had been found with the marks of torture on his body and bullet wounds in his leg.

CORRY: My husband was a museum curator who wrote and sang protest songs. The Indonesian army suspected him of separatism and resistance.

FREEDOM FIGHTERS

RAKI: The struggle for freedom, Papuan culture, and identity are the most important themes in our lives, along with my father’s role in Papua. After his murder, he became a legend. We tried to learn as much as we could about that.

CORRY: Even when they were little I told them: “You have to continue your father’s work.” Eventually they started sharing the story. Raki now travels the world to tell it.

RAKI: The suffering and grief didn’t end with decolonization. The ethnic violence continues. Instead of focusing on integrating, we are resistance fighters, because it is too painful to look away from the suffering going on there. The sense that we have to make so many sacrifices has shaped my life. The story didn’t end with my father. Generations of Papuans after him have resisted the human rights abuses. That resistance, that longing for freedom, carries a huge cost. And those traumas… they remain. You don’t get to heal because you have to keep speaking up. We Papuans want the Netherlands − and the world − to see how resilient we are, and that despite all the misery there today, we are working to build a more hopeful future.

*New Guinea was a Dutch colony until 1962. Because of political developments and pressure from the United States, the Papuans never received the independence they had been promised. They feel abandoned by the Dutch government.

A HEAVY BLANKET

BECOMING AWARE

MILOU: My mother started taking me to the annual commemoration for the women’s camps when I was very young. After I left home, I decided to keep attending because I think that it’s important that we remember together. I recently watched a documentary about the women’s camps. It was only then that I truly realised just how horrific the Japanese occupation must have been, both for my grandmother who was in a women’s camp and for my grandfather who was a prisoner of war.

EEFJE: Growing up, I was not aware of how close the war still was for my parents. That realization only came later. During my studies, I became motivated to look into my own background. This made me very conscious of my Indo-Dutch identity and the impact of my parents’ experiences on me.

STIFLED EMOTIONS

EEFJE: My mother always put on a brave face and got on with things. My father just kept going and never complained. These coping mechanisms helped them to survive both during and after the war. Emotions like anger or sadness were never expressed in our home, but they were very much present. To me, it felt like a heavy blanket.

MILOU: I think my mother carried that heavy blanket with her, and you could also feel it in our home. Emotions were felt, but not expressed. That still plays a role in our family. I also prefer to keep my sadness or emotions to myself, rather than burden others with them. I’m sure that this is something I picked up from my mother.

GUILT

EEFJE: A friend once said to me, “I see so much sadness in your eyes.” That made me stop and think. I realized it wasn’t really my own sadness; it was my parents’ grief that made itself so strongly felt in our home. Through a family constellation session [a method for uncovering hidden family dynamics], I learned how to hand that sorrow back to its rightful place. Even now, though, I notice that when something wonderful happens, or when I feel completely happy, these positive emotions are immediately followed by a sense of guilt.

MILOU: Because my mother is so involved in commemorations and talks openly about these issues, much more is now open for discussion. It’s easier for us to talk about where certain traits really come from. My mother had far fewer opportunities to have these conversations with her own parents.

LOVING

MILOU: My grandparents were gentle people. I really admire my grandmother. Despite everything she went through in the women’s camp, she never became bitter. She was always there for others. It proves how strong her character was: despite everything she endured, her loving nature stayed intact. She didn’t pass the harm she suffered on to her children.

My mother is just as warm-hearted. That bitterness from old wounds has never really taken root in our family.

Tony, 77 years old, second generation

Son David, 52 years old, third generation

Grandson Otis, 13 years old, fourth generation

WE ARE PROUD INDOS

JAPANESE OCCUPATION

OTIS: It’s a pity that I haven’t been taught anything about Indonesia or the war at school. If I want to know something, I ask Grandpa. I’m glad that he was born after the war and didn’t have to experience it.

DAVID: There are still many gaps for me and my father.

TONY: My father was a soldier in the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL). During the war, he had to do forced labour as a prisoner of war on Sumatra, working on the Pakan Baroe railway. My mother, as a non-internee*, often smuggled notes or food into the camp for the women who were imprisoned there. After she was caught, she was also sent to a camp, where she became pregnant by a Japanese soldier. The child died; that’s all we know.

INDONESIAN

TONY: My father was Dutch, and my mother was Menadonese**. I was and felt Indonesian, because of school and the films about the Indonesian struggle against the Dutch. My parents had a good relationship with my mother’s family and chose Indonesian citizenship. They received protection from my mother’s brother, who was a colonel in the Indonesian army. When the political climate changed under President Sukarno, my uncle said: “Go to the Netherlands, or you’ll become second-class citizens.” In 1959, when I was twelve, we were among the last to leave for the Netherlands, as so-called “repentant returnees”.

BEING CALLED NAMES HURTS

TONY: I saw the move as an adventure. But I soon found out what it really meant. We were put up at a guesthouse in a farming village, where I was called names like “peanut, peanut, poo-Chinaman.”*** I couldn’t take it and fought back. Then the parents would show up, saying: “What are you doing here? Go back to your own island, you bunch of monkeys.” It was a terrible period. My father was often sick, and it was hard to see him in so much pain. He had been looking forward to his retirement but passed away at the age of 65.

IDENTITY

DAVID: In the 1980s, I became a fan of political hip hop. I discovered the African-American struggle and became interested in Martin Luther King and especially Malcolm X. This led me to delve into my own roots and I began to feel more Indo. I expressed this feeling through my graffiti on walls: Asian X.

TONY: I regularly came across graffiti by David in Den Bosch. As a child of two cultures, I’ve been searching for that connection with other Indos and Moluccans since I was young.

PRIDE

TONY: When we arrived in the Netherlands, I often felt that the Dutch saw Indos as failures and discriminated against us. Our parents always said: “Do your best at school, and don’t let them push you around.” I am and remain a proud Indo.

DAVID: We constantly have to insist on the correct use of language. The word ‘Indo’ always needs to be explained. People still say: “Indian, Indian-Dutch, or Indonesian.” But I recognize and feel that proud side. I am passing that on to Otis now.

OTIS: I really hope we can go to Indonesia next summer to see where Grandpa comes from.

TONY: What I sincerely hope for the future is that the current generation, free from our burdens and discrimination, will continue to express our identity with pride.

*Non-internees were Indo-Europeans who were not interned. It was often mistakenly thought that they did not suffer much during the war. In fact, they also had to deal with exclusion, scarcity, and repression. After 15 August 1945, with no camps or guards to protect them, they were defenceless against hostile nationalists fighting for independence.

**A resident of Sulawesi.

***The term ‘pinda’ meaning peanut was once used as an insult for people of Indo descent. Nowadays, it is sometimes used by the younger generation as a badge of honour.

IT’S NEVER TOO LATE

STRUGGLES

JEREMY: As a child, I didn’t think much about my family history, but I always had a lot of questions. My parents weren’t very open about their feelings, and I found that hard to deal with. I often wrestled with myself. So I made a conscious effort to change. It’s so important to allow your emotions and talk about them. Once I started doing that, my life felt much more balanced.

MEITY: My father was thirteen and my mother eleven when the war broke out. Not long after the Japanese invasion in 1942, the Kempeitai, the Japanese military police, came to their door looking for “comfort women” * for the brothels. To escape that fate, my mother had to go into hiding for a long time as a “non-internee.” ** Because of that experience, she struggled her whole life with a deep sense of uncertainty, never knowing what might happen next. After the war, they had to seek refuge in protection camps***. From the stories my parents shared, it was clear that the war years were full of hardship, terror and violence.

REPATRIATES WITH REGRET

MEITY: My parents met after Indonesian independence. They got married and had five children. At one point, they had to choose between becoming Indonesian citizens or keeping their Dutch nationality. At first, they chose to become Indonesian. But because they and my brothers faced discrimination, my parents decided to move to the Netherlands in search of a better future. Their application was rejected three times. In 1964, shortly after I was born, they left their homeland as some of the last so-called “spijtoptanten” (repentant repatriates).

BREAKING AWAY

MEITY: My mother was caring and always worried about her children. She was loving, but the thought of letting us go frightened her. Even so, my parents allowed me to study abroad. I was only eighteen at the time. After finishing my studies, I spent a year living in Indonesia.

JEREMY: I experienced exactly the same with my mother. Staying close by and coming home on time sounds all too familiar to me. I moved to Gelderland when I was about twenty-one.

I’LL DO THINGS DIFFERENTLY

MEITY: I always said, “I’ll do things differently,” and I truly believed I was giving Jeremy more freedom. But that’s not how he experienced it. My mother was all about not complaining and just getting on with things, and I copied that approach. At some point, you come up against yourself. Your family history lives within you, both the beautiful parts and the painful ones. The painful parts are hard to let go of. Jeremy says, “I eventually taught myself how to do that.” I’m proud of you, son. I’m sorry I couldn’t do more to help. But it’s never too late. It’s hard to let go, but it is still possible.

JEREMY: It’s important to learn from your past so you can ultimately be yourself. I always try to see the positive in things, no matter how difficult that is.

MEITY: When my parents were elderly, I interviewed them and recorded their stories. Now is the time to share their story with my family, especially with Jeremy, so we can grow even closer together.

*“Comfort women” were women, mostly young, who were victims of wartime rape and forced prostitution during the Japanese occupation.

**“Non-internees” (buitenampers) were Indo-Europeans who were not interned in camps; it was often wrongly assumed they suffered little during the war. In fact, they faced severe hardship, exclusion, scarcity, and repression. After 15 August 1945, with no camps or guards to protect them, they were defenceless against hostile nationalists fighting for independence.

***Protection camps were shelters for Dutch and Indo-European civilians after the end of World War II that were set up in response to the increasing violence linked to the Indonesian struggle for independence.

EEN VERZWEGEN VERLEDEN

A SILENCED PAST

A NAME WITH A PAINFUL LEGACY

My grandparents on my father’s side emigrated to the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) in 1927 to work as teachers in Yogyakarta. As a teenager, I became curious about my background and began researching my family tree. But my grandmother always avoided any discussion of our history, especially when it came to my grandfather, Heiko.

All I knew was that as the eldest grandson, I had been named after him, and that he had drowned in 1944 during a Japanese sea transport when the hell ship Junyo Maru was torpedoed. My grandmother rarely visited us, usually only for birthdays. I remember that whenever my name came up, she would briefly flinch, as if to say, “Oh right, that name: Heiko.”

FATE

Because years of service in the tropics counted double, my grandfather was eligible to retire at fifty. The family had planned to return to the Netherlands in the summer of 1940, but the German occupation made that impossible. My grandfather joined the city guard in Yogyakarta to support the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL) in defending the city.

After the Dutch East Indies surrendered, the Japanese occupiers classified him as a military officer and took him as a prisoner of war. My grandmother, along with her daughter and youngest son, was sent to a women’s camp. Their eldest son, my father, had already returned to the Netherlands in 1937 at the age of fifteen to attend high school. My aunt, who was eighteen at the time, was abused and tortured in the camp by Japanese soldiers. She endured horrific experiences. My uncle, just sixteen, was sent to a boys’ camp, where he was forced to bury the dead from the sickbay.

THE GREAT SILENCE

Like my grandmother, my father, uncle, and aunt never spoke about their wartime experiences in the Dutch East Indies. They always said, “We have nothing left from our time in Indië.” My father said this many times. In 2008, when I was invited to speak at the commemoration for the victims of the hell ships, I told him, “The title of my speech is: How do you tell a story you don’t know? Because you always say there’s nothing from Indië and have never wanted, or been able, to share anything real about that time.” To my great surprise, a few years after his death, I discovered 299 letters from my grandparents to their families in the Netherlands. He had kept them. For me, they have come to symbolize the great silence. But it’s also painful, because I had believed my father [when he said there was nothing left from that time]. Since 2012, as founder and chairman of the Foundation for the Remembrance of Victims of Japanese Sea Transports, I have spoken about that silence many times in public.

A LIFE-SHAPING PAST

Now, at the age of 70, as I reflect on my life and my work as a geneticist and therapist, I can clearly see how the past has shaped many of my choices, often without my being aware of it. The unanswered questions and gaps in my family history led me to explore what is now known as the transgenerational transmission of trauma. Over the past fifteen years, I have come to understand how deeply that silenced past has influenced both my personal and professional life. At every annual commemoration, I hope that young people come to see how their family’s history helps shape who they become, and that talking about it truly makes a difference.

CONNECTION

ATTACHMENT

LISA: My sister and I were adopted from China. Attachment is often an important theme for adoptees. I talk about it with my mother, who knows what it’s like to experience distance within a family. She used to go for years at a time without seeing her father.

DIDO: I’m quite introverted, and Lisa is very extroverted. I’ve learned a lot from Lisa, thanks to her questions about my complicated relationship with my father.

LISA: We both find that there’s a lot of ignorance in the Netherlands about our histories. Both Mom and I have been confronted with prejudice or, in my case, outright discrimination.

TWO WARS

DIDO: Similar to so many other families, we hardly ever talked about the war years. My father volunteered for the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL) in 1939, but was captured by the Japanese in 1942. After enduring a brutal, weeks-long journey on a Japanese “hell ship” (a transport vessel), he was taken to Japan and forced into labour. Following the liberation in 1945, the Indonesian War of Independence erupted, and he was sent back with the KNIL to fight against the Indonesians.

A SADISTIC STREAK

DIDO: My father was a difficult man, and I believe he came back from the war deeply traumatized. He could be incredibly sadistic at times. For instance, I was a slow eater as a child, and even though I was still very young, he would call the police every day to come and take me away. The first things I inherited after his death were a klewang and sabers—traditional swords. That did not feel like a welcome inheritance. Of course, you want to think well of your father, but it’s not always easy. When you start digging into the past, you can’t help but wonder what he must have gone through.

MY OWN PAIN

DIDO: My parents divorced when I was seven, so my relationship with my father was fractured. Sometimes we went years without contact. Once, he sent me a newspaper clipping about visiting the family of the American pilot who had flown over his camp in 1945. It would have been the perfect moment to ask, “Dad, what was it like there? How did it feel?” But I never asked. And I’ve carried that with me. What stays with me isn’t just his silence, but the fact that we never had those conversations, and that I was also partially to blame for this.

LISA: I’m very curious by nature, so I think it’s really important to ask Mom lots of questions. Hearing her share these things about herself has made me even more aware that I need to keep doing that.

PRIDE

DIDO: I’m very proud of my family and my books. Lisa and I both have Asian roots, and our own separate wounds. Talking about them deepens our connection.

LISA: Maybe writing a book about her father was confronting, but it was her way of getting closer to him: and to herself. I think it lifted a weight off her shoulders. It has also helped me to understand Mom even better.

DIDO: I hope that my daughters will find a lot of happiness in their work, just as Auke (their father) and I, both writers, have done. This is how we express ourselves and shape our thoughts and emotions. It’s only now, as I’ve become older, that I have really found my own voice and found a way to process my old pain.

STIFLED AT THE ROOT

A LIVING HELL

MALU: I never knew my grandfather, and my grandmother always used to say: “I don’t remember anything, ask someone else.” But now I have a child of my own, I’m becoming more curious.

ARNOLD: I, too, was told almost nothing. My mother was fourteen when she was interned. After his parents’ divorce, my father was sent to live with his grandparents. He had to drop out of secondary school because they could no longer afford the fees. That was a terrible blow for him. At twenty, he joined the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL). During the Japanese occupation, he ended up in a POW camp at the age of twenty-one. He was forced to do slave labour on the Pakan Baroe railway in Sumatra. It must have been a living hell.

A DISTORTED IMAGE

MALU: In 2008, I visited Sawahlunto − where my grandparents used to live − together with my parents and cousin.

ARNOLD: I used to think back to that time with a kind of tempo doeloe nostalgia. But after reading Japanese Eyes by Reggie Baay, that view changed completely. In early 1947, there was a five-day battle near Palembang where around five thousand civilians were said to have been killed. I had to make a major mental shift: is it possible that my father, who was stationed in Palembang at that time, had also killed people? That question still haunts me. My parents fled Indonesia in 1952, leaving in haste out of fear for their lives. Indonesian nationalists were targeting Indo-Europeans who had not chosen Indonesian citizenship. After arriving in the Netherlands, we lived in three different contract pensions and were extremely poor.

FEAR AND PANIC

ARNOLD: In 1999, I suffered a heart attack. Malu, still just a little girl, stood by my hospital bed. Later, when I began experiencing panic attacks, I realized I needed professional help and went into therapy. My psychiatrist uncovered a deep-rooted fear linked to my past: “You were born at a time when your mother was still haunted by the trauma of two wars, living in fear of her life, and, above all, having to confront the fear of moving to a strange country.” That fear, I’ve come to understand, lives on in me as well.

MALU: Even though I was young, I always felt this undercurrent of fear, even though much of the past was kept hidden from me. Around the age of twelve, those fears started playing a major role in my own life, and I suddenly began having panic attacks.

ARNOLD: Malu, young as she was, said: “I can’t handle this anymore. I need help.”

MALU: Therapy helped both of us keep those feelings fairly well in check. Nevertheless, in our little family unit of three, fear and panic were a constant theme throughout my childhood.

CLEARING THE WAY

MALU: I think it’s important that our son Indy learns something about his Indo heritage. What he does with it is up to him. I’m lucky that my father worked so hard on this, and on himself. That has already cleared a path for me.

ARNOLD: I now feel truly ready to be a grandfather. I just hope for the little katjong (Indo boy; teasing term) that the fear really does stop here. Only then can he really be open to what the world has to offer.

A LIFE WITHOUT BITTERNESS

GRIEF

MARY: I was very young when I arrived in the Netherlands in 1951. It was only later that I understood what my parents had endured. I grew up in Woonoord Westerbork, a former concentration camp, where the men were not allowed to work. In our barrack, there were photographs, but no one spoke about the past. I could feel the sorrow and longing for their families. Even happy memories were not shared; everything was buried under homesickness and pain.

DIGNITY

MARY: There was a great deal of solidarity among us, and the church and music played an important role in our lives. But the men were deeply frustrated because they had been made completely dependent. Their dignity had been taken from them, and they lost faith in the Dutch government. They used to take out their frustrations on the children. We were raised in a strict, militaristic manner and were often subjected to corporal punishment.

FEAR

MARY: During the war, my mother had often had to hide from the Japanese and witnessed many acts of cruelty. The fear she carried in her body was still very much present. The Dutch government had placed Moluccans from different kampongs (villages) together in the residential camps. Since they didn’t know each other’s customs, conflicts and brutal situations would arise, which meant that we children often lived in fear.

PALPABLE

LISA: As a child, I didn’t really think about what my family had gone through. It wasn’t until the train hijacking in the 1970s that I was suddenly confronted with my Moluccan identity. From that time on, I began to delve into our background. The thought of my mother arriving at the port of Rotterdam as a two-year-old moves me deeply. Now that I know all the stories, I have a clear image of all the history she carries with her, and I can feel her pain.

SOCIAL PRESSURE

LISA: As the oldest grandchild, everyone expected me to set a good example. They would say, “Don’t embarrass us.” Not that I ever did, but there was a lot of pressure to fit in. I had to learn how to speak up and share my own opinions. I also wanted to take my singing talent beyond the Moluccan community, but that wasn’t something my family and friends supported right away. By the time I was nineteen, I knew I wanted to leave home.

MARY: I was absolutely shocked and asked Lisa, “Don’t you like it here?” She replied that she felt suffocated and couldn’t breathe. I decided to support her and let her go.

BREAKING AWAY

LISA: When I turned 35, I realized I needed to make some new choices. The pressure and responsibilities from my family, job, and singing career were overwhelming me. Even though I had a close bond with my mother, I tried to explain to my parents that I wanted to live my life on my own terms.

MARY: I had to fight for my children, even at a young age. For example, I decided we had to move out of the Moluccan neighbourhood and also made my husband realize that it’s the children who are important. It’s not about us; they need to move forward!

LISA: It’s important to us, the third generation, to honour Moluccan traditions in our own way. I’m extremely grateful for the stories and for the fact that my grandparents did not pass on any bitterness to us, despite their old pain.

Hedwig, 89 years old, first generation

Daughter Monique, 59 years old, second generation

Grandson Marius, 24 years old, third generation

LIVING IN FREEDOM

WORLD HISTORY

MARIUS: In recent years, my grandmother has started sharing more and more with me. Before then, I had no real sense of her past. It’s very hard to truly grasp how long the period of war in the Dutch East Indies and Indonesia lasted, and how deeply it affected everyone who lived through it. It really moves me.

MONIQUE: When we were young, family gatherings were all about small talk. I could tell my grandmother didn’t want to talk much about “Indië”: the stories were just too painful. She had chosen to focus on the future, not dwell on how terrible the past had been.

HEDWIG: I believe that it’s important for my descendants to know about our past. It’s part of world history, and people should be more aware of it.

NON-INTERNEES

HEDWIG: My father, who worked at a bank, was called up in early 1942 to serve in the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL) as the threat of war grew. When war broke out, he was immediately taken prisoner by the Japanese and deported on a “hell ship” to Burma, where he was forced to work on the Burma–Siam railway. He spoke of it only rarely. Because of my mother’s background, we were classified as “non-internees.” We survived thanks to the fruit trees in our garden and the kindness of our Chinese neighbours, who secretly brought us food at night. After the war, my father refused to demobilize. During the second “police action”**, he was sent to Malang. That was a very difficult time. The pemuda (Indonesian freedom fighters) could appear anywhere and were extremely dangerous. We were taken to school in trucks, escorted by armed soldiers.

CAREFREE

MONIQUE: Because of all the stories about the two wars our family experienced, I’ve always been deeply aware of how carefree our own childhood was. I hope my children get to enjoy a childhood that is just as peaceful as ours.

MARIUS: What stands out for me is that Mom and I both grew up in a very safe environment. That’s pretty special. When you look at world history, this is the first long period of true peace. I can now understand that Grandma, having never experienced that herself, is only just beginning to express herself.

FREEDOM

MONIQUE: We learned not to judge too quickly or to put people into boxes. People can only flourish when they feel comfortable around you.

MARIUS: That’s why I’ve come to really value what it means to grow up in freedom: being able to do what I want, be who I am, and even make mistakes. Plus always having my parents and grandma to fall back on. That warmth and sense of safety is something that I want to pass on to future generations.

MONIQUE: We chose a life in music, which is such a beautiful profession. It puts everything into perspective. Thanks to the success of our band, Loïs Lane, which I shared with my sister Suzanne, we were able to create a good life for ourselves: relaxed, being together, and enjoying the little things in life in a positive way.

MARIUS: Now that Grandma sees that we’ve all turned out well, she feels more able to open up about the pain from her past.