In the exhibition I take care of you, you can see and read the stories of fourteen Amsterdam residents. The portraits and stories show that informal carers are never the same: young or old, from different backgrounds and with different reasons for caring. But they all have one thing in common: the dedication with which they care. Read the stories of Leontien, Kadi, Frits, Saadia, Málene, Marlanda, Michael, Sevim, Fiza, Ton, Vera, Veronica, Jim and Myra here.

Leontien (54): She has made me kinder, stronger and wiser

My life and even my identity changed completely after the birth of my youngest daughter. I used to work for the local council in a senior position. But when she was born with a disability, I decided to stop working. Caring for my daughter was incompatible with my job. I went back to school and now work in healthcare. Here, I can use my experience to support parents with a child with a disability. Because I know how it feels: you have to reshape your entire life.

Many people think you get used to it. But that’s not true. The pain remains. You don’t lose a person, but you lose pieces of the future. What you thought would happen didn’t happen. That’s called living loss. The sadness keeps coming back: on birthdays, at the end of primary school, during puberty, or simply when dreaming about the future.

The process of coming to terms with that loss feels lonely. People around you rarely ask how you’re really doing. That’s exactly what I needed. Ask about the sadness. If I can talk about it and don’t have to brush it aside, then it’s allowed to be there. That makes it less difficult.

I am protective of my daughter. She needs people who really know her and are always there for her. You find those people mainly in the family, such as her brother and sisters. In healthcare, that is more difficult, because the people involved often change. Although we are now blessed with a wonderful woman who accompanies her every week through the Personal Budget scheme. She has become her best friend. She takes her out into the world. That is extremely valuable.

It has brought me a lot. I look at the world differently. My daughter teaches me to slow down, to look differently. Through her, I see the value of vulnerability. She has changed me. My daughter’s disability has removed a layer from me. She has made me kinder, stronger and wiser.

I would like society to make more room for people like my daughter. Nowadays, it is often a case of hiding away and looking the other way. But vulnerability can also enrich your life. For example, when my daughter gets very close to someone or asks direct questions, I see people becoming uncomfortable. But that discomfort is not hers – it is often the other person’s. My daughter disrupts. She does not fit into what people are used to. And that affects you. I hope more people dare to see that. It would make the world a little bit better.

Kadi (24): Appreciation helps me

Being a carer means that I am always alert. I feel responsible for my mother day and night. There is little room to distance myself or be truly free. People who work in healthcare can go home after their working day. But for me, caring only begins when I get home from work or school.

Shortly after my father passed away, my mother suffered burns to 45% of her body in an accident. Our lives have changed since then. The roles have been reversed: I now take care of her, even though I myself have a muscle disease and am in a wheelchair. I love my mother, but it doesn’t feel like a choice, more like a necessity. That’s mentally tough.

My mother lives at home and fortunately has a care team that helps with physical care 24 hours a day. Still, there are many other things I take care of: administration, appointments, schedules and cooking. Because I live at home, a lot falls on me. My sister also helps, but she lives on her own. We call each other every day and she comes to help when needed.

Most of my family members live in Curaçao. As a result, the care mainly falls to me and my sister. All the stress has caused my health to deteriorate. My GP referred me to a psychologist. It turned out that I have post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), partly due to my past. My mother was already ill and partially blind before the accident, so I had to take on a lot of care responsibilities at a young age. Now I am learning to set boundaries. I find that difficult, because I sometimes feel guilty, but it does help me.

I am proud that I was able to motivate my mother to rehabilitate. She now occasionally tells me that she is happy with what I do for her. That is nice to hear, because I often feel invisible. More appreciation helps me.

I would like to have my own place, to live on my own. It’s not easy to tell my mother that, but I’m ready for it. I want peace and quiet, the occasional day without worries, time for myself, to meet up with friends and live my own life.

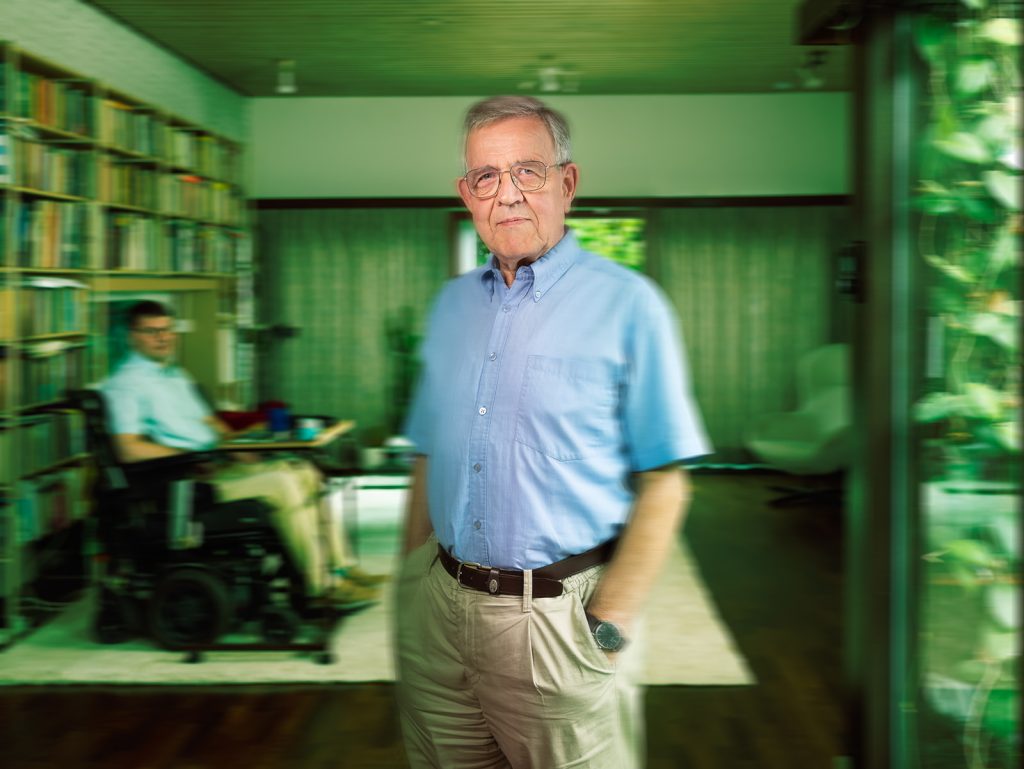

Frits (77): Without love, you can’t keep up

I am retired and always did a lot of volunteer work. An asylum seekers’ centre has been set up here in the neighbourhood and I would really like to help out there. But my days are now completely taken up with caring for my husband, Jürgen.

Jürgen is 29 years younger than me. When we moved in together, I already knew he had MS. But at the time, he was still very fit. He could still jog and easily outrun me.Unfortunately, his condition deteriorated rapidly. Now he can’t really be on his own anymore.

Home care comes every day to help him shower and get dressed. But I do everything else myself. I get him out of bed, put him on the toilet, help him eat, take him outside and put him back to bed. It is very intensive. Sometimes it takes half an hour just to put him on the toilet. It is constant care, all day long.

This situation has changed our relationship. We are no longer equals as we used to be. That’s difficult. Jürgen is completely dependent on me. I often speak on his behalf in conversations with others. I sometimes wonder if I’m doing the right thing. Fortunately, we can also joke about it and laugh together. And there is a lot of love between us. Without that love, this would not be possible.

What I have learned is that I need to pay close attention to my own limits. I also need time for myself. People often don’t know what kind of help they can offer, but if you ask them to help, they are happy to do so. An older couple from the neighbourhood comes by once a month with a nice meal and we eat together. That’s really nice, because then I don’t have to cook. And it’s fun.

But taking over the care for a short time is difficult, because you really have to learn some things. Like working with the hoist or emptying the urine bag.

We have a Personal Budget (Pgb). This allows us to arrange care ourselves. I’ve come up with something that works very well for us. We have five students who each come to help one day a week. They know Jürgen well and feel almost like family. This allows me to go to a concert, museum or just relax sometimes. Sometimes I stay at home and have them make me a sandwich. That’s really enjoyable.

Saadia (49): Mum, don’t forget to take care of yourself

I grew up in a small village in southern Morocco. There, people naturally look after each other. For elderly people without children, one neighbour cooks on Mondays, another brings couscous on Tuesdays. That way, someone comes by every day. It’s really a “we culture”. You help each other. Now that I live in the Netherlands, I do the same. Helping neighbours, being there for the elderly: I do it with love.

I am a carer for my son, who has a chronic illness and is often in a wheelchair. Sometimes he has seizures and then he needs me for everything. I am a widow and a single mother. When my husband got cancer, I was still working, but I couldn’t combine it with caring for him and our two small children. He passed away in 2014. This was followed by a sad period because several family members died. Still, I kept going, for my children. They deserve a happy childhood.

For people with a migrant background, asking for help is particularly difficult. The language is difficult, forms are complicated, there is mistrust towards authorities and talking about problems is often taboo. With the Aknarij West foundation, I have been committed to women’s emancipation for years. Since my husband passed away, I have focused primarily on supporting informal carers: reaching out to them, informing them and assisting them. I help informal carers find the right kind of help and offer a listening ear. At our support centre, informal carers can meet each other and safely share their stories and experiences.

I don’t readily ask for help or complain. But I have learned that it is important. Sharing your story with others and listening to people who are going through the same thing is a relief. I encourage others to take good care of themselves, even though I sometimes find that difficult myself. My daughter now helps out and often says, ‘Mum, don’t forget to take care of yourself.’ Sometimes I manage to do that: go to the gym, go swimming or watch a film together. But the worries remain. You wear a cloak of care, it weighs on you, but above all it is about giving love to your loved ones. I see it as a gift and a sign of Allah’s love.

Malène (65): I worry all day long

I worry all day long. It never really stops. Of course, I go to work as usual. And in the evening, I sometimes sit on the sofa with my husband watching a series. But even then, I think about my 26-year-old son. Only when I know he’s home can I sleep peacefully. That’s why he’s been sleeping with us again recently. At least then I know he’s still alive.

He has mental health problems and multiple mental health diagnoses. He is also addicted to ketamine. It is difficult to find the right help, and that is frustrating. Care providers usually look at what their own organisation can offer, rather than what someone needs. For example, you have to be clean before treatment can start. But his addiction is also a result of the long wait for help.

My husband and I now do a lot ourselves. We listen to him and are there for him. It’s taking care of him and worrying about him. But we also have to take good care of ourselves. That doesn’t always work.

I am trying to let go more and more. I manage to do that a little when I am at work or when my son is safely in bed. Writing down my life story also helps. I am a KOPP child myself: a child of a parent with mental health problems. My past still plays a role in my life. That hurts. Sometimes I feel guilty, as if I have passed things on.

People often forget that caring for a child with mental health problems and addiction is also informal care. If your child is in a wheelchair, for example, the need for help is clearer. With mental health problems and addiction, there is less understanding. You cannot see the illness. As a result, these informal carers often remain invisible. And that feels lonely.

I work at Cliëntenbelang Amsterdam. We are committed to improving care and support for informal carers. So I know exactly what help is available. But when you are emotionally involved, you often forget that you are also allowed to ask for help yourself. Your head is just full.

Our son recently got a client support worker. That helps. They go to appointments with him. That’s nice, because the support worker can remain objective. My emotions get in the way.

Marlanda (71): Don’t forget to buy yourself a bunch of flowers

All my life, I have been there for others. It’s in my nature. I have worked for various organisations, including as a volunteer. Volunteering is part of my life. I have set up many projects, especially to combat loneliness. Now I am working on something new: a boxing project. It is specifically for people with disabilities, Parkinson’s or chronic illnesses who want to keep active. Exercise helps so much, mentally as well.

My husband fell ill in 2022. He often lost his balance. He fell off his bicycle more and more often in the street. The diagnosis was severe: Parkinson’s disease. And then there was the rare and progressive variant PSP, which causes his health to deteriorate rapidly. Since then, I have been taking care of him. I help him with his personal care: showering, dressing and eating. Then I take care of the administration. Everything falls on me, because he can no longer manage on his own.

I do this out of love. I have a wonderful husband who has always been very good to me. But it can be difficult at times. Finding good support is hard. I ask for help, but that mainly results in hassle and frustration. Few people take the time to really listen. But sometimes I meet someone with a warm, empathetic heart. Then I immediately think: ‘This is a good one, I want to keep them!’

My husband’s eyesight is getting worse. Fortunately, we have now received aids from Bartiméus. Such as a reading computer that helps him read. I hope our grandchildren will come and help him read from time to time. That’s also fun for grandpa.

Together, we remain active. My husband accompanies me everywhere: to volunteer work and meetings. We ensure we get exercise, which benefits both of us. We walk and dance. My husband enjoys music and has a large record collection. Boxing brings us joy. This is due to the production of dopamine.

I realise more and more that I also have to take good care of myself. I am quite spiritual and meditation helps me. Sometimes I look in the mirror and say, ‘Love yourself more.’ I also say that to my husband: ‘Look yourself in the eyes. Talk to your soul. Then you will feel what you need again.’

He still supports me in his own way. Sometimes when I go out, he says, ‘Don’t forget to buy yourself a bunch of flowers.’ That small gesture means a lot to me. That’s how we take care of each other, in our own way.

Michael (37): Caring, worrying and missing care

I was just a child when I started caring. My younger sister was born with a rare syndrome. She has a very severe intellectual disability with difficult-to-understand behaviour. At home, everything revolved around her. My parents and I formed her care team. That felt very normal to me, but it also meant that I had a lot of responsibility at a young age.

I could often understand my sister better than anyone else. Just by looking at her hands, I could tell if she was tense and might have an outburst. That’s why I stayed at home as long as possible in the mornings to help my mother. After school, I went straight home. I learned to be independent at a young age and basically raised myself. I didn’t pay much attention to my own feelings. I didn’t share them with my parents either, because I didn’t want to burden them even more.

I was quiet at school. I had few friends. There was simply no room in my head for friendship or romance. My adolescence was dominated by worries, not by discovering who I was. That came much later.

When my sister left home at the age of twelve to move into a residential care facility, I felt a sense of relief. However, it was only when I went abroad a few years later that I truly felt liberated. There, I got to know myself away from all my worries and finally gave space to my feelings for boys. Discovering my queer identity was something I hadn’t had the time or space for before.

When I turned eighteen, I officially became my sister’s care mentor. My parents helped me a lot with that decision. That was very important for my own process. Still, it was obvious to me, and it didn’t really feel like a choice.

For a long time, I thought I didn’t need any help. But I really struggled. During my first job after graduating, my father fell ill. Caring for him was on top of my work and caring for my sister. That’s when things went wrong. My psychologist taught me something valuable: you also have to take good care of yourself.

Together with other organisations, I am committed to raising awareness of young carers. Many young people provide care quietly, without others noticing. They care for others, worry about them and miss out on care themselves. I recognise this all too well.

In my work with the Alliance for Young Carers, I talk to young people and people who work in education, healthcare or local government on a daily basis. I want the people around them to understand what it does to you when you care for someone at such a young age. And I want people to understand that they can also make a difference for these young people. Because you don’t have to do it alone.

Sevim (63): I am quite proud of myself

For me, it is natural to take care of your family. That is what I learned at home and it is part of my culture. In Turkey, your parents take care of you first, and later you take care of them. I took care of my mother for years until she passed away, and now I take care of my father. You also continue to take care of your children for as long as necessary. My 38-year-old daughter has a disability and still lives with me. I have taken care of her her whole life. As a single mother, I also enjoy having her live with me.

Still, I notice that it is becoming more difficult as I get older. Not so much the practical care, but the worrying: What if I can no longer do it? Who will take over? I don’t want to burden my other children with this – they have their own lives too.

Every month, I go to the informal carers’ lunchroom in my neighbourhood. There, I talk to other informal carers and sometimes we do meditation. Having some time for yourself and being able to share your story is so important. People who are going through the same thing understand each other. A listening ear or a hug can make a big difference.

I see that many informal carers do not take enough time for themselves. Sometimes they do not know where to find help, or they find it difficult to ask for help. For many people with a migrant background, the threshold is even higher, due to language, shame or taboo. At the informal carers’ lunchroom, I am the only one with a Turkish background. You really want more people from culturally diverse backgrounds to find support here.

Caring for my sick mother and my daughter was a lot. After my mother passed away, I took a small step back. Fortunately, my father is fairly independent. He goes to the Dynamo men’s group three times a week and to the neighbourhood restaurant at Kraaipan once a week. He really looks forward to it – he is often ready an hour in advance.

Caring is not only part of my culture, but also part of my character and heart. In addition to my informal care, I teach Zumba classes to women in the neighbourhood and exercise classes to Turkish and Moroccan grandmothers. Their smiles and gratitude give me so much positive energy. I am actually quite proud of myself.

Fiza (24): When people stare at my little brother, I just stare back

I grew up in a loving family, but also with a lot of responsibility. As a child, I was quiet and independent. I didn’t ask for much attention, because I felt from an early age that I had to take care of things. Especially my little brother.

My little brother is now 22, but he functions like a three- or four-year-old. He needs help every day: with eating, showering, brushing his teeth and making plans. When we go somewhere, we have to prepare him well.

I used to be afraid to talk about how I felt. I didn’t want to burden my parents even more. I didn’t always feel understood by my friends either. I couldn’t really talk to anyone about it. It was only when I started talking to a psychologist that I learned to set better boundaries. That helped me a lot.

As a Muslim, I believe that everything happens for a reason. In my faith, people with disabilities are seen as innocent and pure. My little brother is closer to God. It is a privilege to be able to care for him. That gives me peace and patience, even in difficult moments.

Now that I am older, I take better care of myself. I travel, try out new hobbies and go out with friends. Sometimes I even travel alone. I didn’t dare to do that before, because I felt guilty towards my family. Now I know that if I take good care of myself, I can also be there for my little brother.

I don’t see myself as a carer, but primarily as a sister. For me, it’s normal to take care of him. But I also know that it can be difficult. It’s important that siblings of children who need care receive support.

That’s why I recently started Bruz Spot with two others: a place for brothers and sisters like me. Once every six weeks, we organise something fun or educational. This allows young people in similar situations to meet, relax and share their stories.

Many people don’t know what it means to care for a brother or sister at home. I also hope that people on the street will show more understanding. When my little brother shouts loudly because of stimuli, people often look at us strangely. That hurts.

But I’m not ashamed anymore. He has a right to be here, just like me. And if they stare, I just stare back. I’m proud of who I’ve become. And that’s also thanks to my little brother.

Ton (70): You need to take action now, otherwise you’ll fall down yourself.

I have enjoyed working at the Rijksmuseum for many years. Even after my retirement, I stayed on as a project assistant. But a lot has changed in recent years. My wife Loes developed Alzheimer’s. At first, we noticed it in small ways. She forgot appointments or what we had just discussed. Sometimes she would get angry when I pointed something out to her, whereas we had never argued before.

After many tests, the diagnosis came: Alzheimer’s. During the coronavirus pandemic, it got worse. That’s why I started working from home more. My employer was very understanding. Loes was even allowed to come to work with me, first to a staff party, later to training sessions. Everyone thought that was normal. If she didn’t come, colleagues would ask about her. I am grateful for that.

For me, the care slowly became heavier and more painful. Our relationship also changed. After 37 years as husband and wife, she sometimes no longer recognised me as her husband. Fortunately, our daughter, my brother-in-law and sister-in-law, and two couples who were friends of ours helped out. We formed a core group to care for her together. One day they said, ‘Ton, you really need to take action now, otherwise you’ll collapse.’ I was exhausted, and they could see that better than I could.

With the help of a case manager for people with dementia, we found a place for Loes at the Leo Polakhuis. She lives in a small group and participates in many activities. Music in particular does her good. She has been living there for eight months now and seems happier. At first she always wanted to go home, but that is no longer the case. She is happy there.

When Loes moved, it felt strange, but also like a relief. I was so tired that it was only then that I realised how hard it had all been. It took two to three months before I regained some energy. Now I’m doing things I enjoy again, such as cycling or going camping.

I don’t feel guilty, but I do feel a kind of obligation to visit her almost every day. Staying away for more than two days doesn’t feel right. Perhaps when she really doesn’t recognise me anymore, I’ll have more space for myself.

I am on the advisory board of Alzheimer Nederland and follow their online meetings. Here you share experiences and advice with other carers. And I write blogs. Sharing my story helps me to get things off my chest. Always with a cheerful note at the end.

Vera (37): Sometimes it’s enough when someone just asks you how you are

I’ve been a carer since I was a child, although I didn’t know the word for it back then. I find it a distant word. There should be a better word for it. My brother and sister have mild intellectual disabilities and autism. Because we often didn’t understand each other, there was regular tension at home. I wanted to help my parents. Tidying up when visitors came. Making sure everything ran smoothly. I quickly felt responsible.

One in four children grows up in a family where someone is ill or needs extra care. So you grow up “in care”. Not always with practical tasks, but with worries in your head. Always alert. You absorb your parents’ tension and stress from an early age. It builds up and gets into your body.

There were carers at home, but they discussed everything with my parents. They never spoke to me. At home and at school, I didn’t ask for attention. I was a quiet child. Precisely because of that, no teacher or neighbour asked me how I was doing. How I felt, with everything that was going on. I often felt lonely because my worries were not seen.

In hindsight, it would have helped if someone had really seen me. Someone who recognised that it’s tough. That as a child, you sometimes carry a lot. When people acknowledge that, it gives you breathing space.

Now my parents have asked me if I want to become a care mentor for my brother and sister. Friends advise me to think carefully — I have a young family myself. But for me, it doesn’t feel like a choice. No one else can do it when our parents are no longer around. I am the one who can do it with love and commitment.

It has also brought me a lot. I have developed a strong capacity for empathy and can quickly sense how others are doing. I have a strong sense of justice and want everyone to be seen, including people who are “different”. That is why I create social projects with my foundation and as a photographer, such as “Do you see me?”.

This project is a travelling exhibition about young carers, combined with guest lessons in schools to make teachers, children and young people aware of what it is like to grow up with extra care for a family member. I hope that young carers will recognise themselves sooner and that they will be seen more quickly by those around them. Because sometimes it is enough for someone to just ask how they are doing. Schools and others in their environment can do a lot for young carers in this regard.

Veronica (62): Asking for help is not a weakness, but a strength

I grew up in Ghana. When I married my Dutch husband, I came to the Netherlands. I am still grateful for that every day: I had my children here and can count on care that might be unimaginable in my country of birth.

Our eldest son was born healthy, but developed severe epilepsy as a baby. This caused him to suffer serious brain damage. He now has multiple disabilities, can do almost nothing for himself and cannot speak. My husband died eight years ago, and since then I have been caring for him on my own. My other children help out, but I don’t want to burden them too much. Above all, they need to be able to build their own lives.

Fortunately, we live in IJburg, in a residential complex for families with children with disabilities. Everything is close by: a school, day care and a guest house. When my son is there, I can recharge my batteries. Those moments give me the energy to help others too.

I know how complicated it is to arrange care. The language barrier is significant for many people in the African community. I was lucky myself: my husband spoke fluent Dutch and understood the rules and conditions. That meant we got the help we needed. Now I want to help other parents with disabled children.

In the African community, there is sometimes shame associated with having a child with a disability. Some parents keep their children indoors. I find that sad. My son cannot speak and is in a wheelchair. People find it difficult when they encounter us together. But I want people to accept him as he is, without pity. He is my greatest concern and my greatest joy.

I took a training course at Markant, an organisation for informal carers. Now I am an ambassador for the African community. I talk to many people and provide information, for example about courses and support for informal carers. I see that training courses for informal carers really help them to manage their energy better. They also learn how to ask for help.

In addition, I try to reach as many people as possible with my drama group and local television programmes on GAM TV – SALTO. This is essential: many people are distrustful or ashamed to ask for help. They are afraid of what others will think and doubt whether care providers can be trusted. Asking for help is not a weakness, but a strength.

Jim (45): Thanks to our care, he can remain in his own home

Two years ago, I spent a lot of time with my father, who had just been diagnosed with dementia. I noticed that he was starting to neglect himself: he ate crisps and chips for dinner, he forgot to tidy up his house and couldn’t always remember appointments. Because I was working less at the time, I took on the care. In the beginning, I did this together with my sister. She took care of all the administration and paperwork. I mainly did the practical care: cleaning, shopping, cooking and keeping a close eye on what my father could still do independently and what he could no longer do.

My father had to get used to my presence. He often asked, ‘What are you doing here every day?’

After six months, I went back to working full-time. My brother, sister and I then drew up a schedule. My 19-year-old nephew saw how much time it took and now helps out too. That’s really nice!

Applying for the Personal Budget and getting permission to spend it was difficult. We lacked a kind of manual for informal carers. We had to figure out a lot ourselves and ask a lot of questions. At one point, we called in a case manager for people with dementia who need extra care.

With the personal budget we receive, we can provide care that suits my father better than home care. Home care often involves a different person coming to visit, which is confusing for him. My father is Chinese and his Dutch is not very good. Communicating with him is difficult enough for us, let alone for a care provider who does not speak his language.

At first, I worried about my father every day. Thanks to a technical solution, we can now keep an eye on him remotely. This allows us to see where he is and what he is doing. We also have a schedule so that someone is with him every day.

Fortunately, he now attends day care regularly. That helps enormously. Among other things, we chose a foundation specifically for Chinese elderly people. They speak his language and understand his culture. He feels at ease there and has social contact.

It remains difficult for us, though. The roles have really been reversed – he sometimes feels like an extra child. But we are glad that we can take care of him this way. His quality of life remains good and he can stay in his own living environment.

Myra (52): I now see how many kind, patient people there are

For me, being a carer means caring for my daughter out of deep love. Sometimes it’s hard, but it has enriched my life. I was able to make the choice to be a full-time mother. I used to be quite shy, but now I have grown into a confident and independent woman who can stand up for her family and herself.

Serah was four years old when she suffered a severe brain haemorrhage. She was on the brink of death. When I was allowed to take her home after a difficult time, I was intensely happy. It was only then that I realised how precious and fragile life is. Serah is now a wonderful young woman. She has a great sense of humour and is always friendly and caring towards others.

Serah uses a wheelchair for longer distances, which is a challenge for her freedom of movement. As a result, she often stays close to us. Then she can go around the block on her own to the baker, butcher or greengrocer. It’s also nice that we live in the Jordaan: everyone knows us and keeps an eye on Serah when she’s out on her own.

To relax, I walk our dog every day. Now I spend at least an hour outside every day. That gives me peace and new energy.

Of course, it can be tough sometimes, because I have to do much more for her than I would for a healthy eighteen-year-old. Still, I prefer to take care of her myself. I just know best what she needs. For a while, we hired someone to support Serah. We got on so well that she almost became part of the family. I am incredibly grateful to her for that, but sometimes it was too much for me. I also need my own space to recharge.

All these experiences have changed my view of people: where I used to be distrustful, I now see how many kind, patient people there are. In healthcare and also just in our own neighbourhood. Thanks to Serah, I see life in a much more positive light – and that is perhaps the most beautiful gift she has given me.